Netflix's new series "The Sons of Sam: A Descent into Darkness" digs into the idea that there's more to the Son of Sam serial killer case we thought we knew . . . and that we're still not safe.

Starting in July 1976, over the course of 13 months more than a dozen men and women in New York were shot in seemingly random attacks. These would become known as the Son of Sam murders after police found a handwritten note left at a crime scene in which the killer referred to himself as Son of Sam and promised the violence would continue.

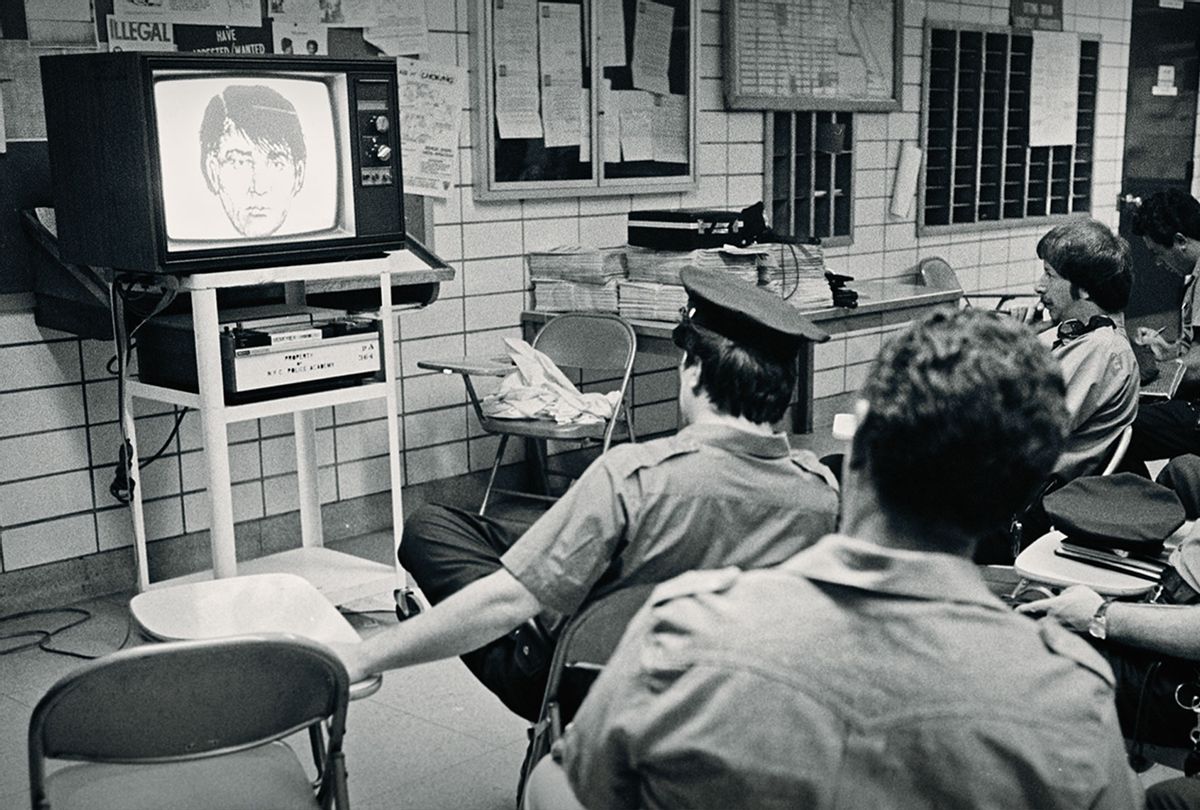

As the city was gripped by growing fear, police embarked on what was then one of the biggest manhunts in the city's history. Eventually, they arrested David Berkowitz, a young man living in Yonkers who greeted law enforcement by saying, "Well, you got me." He would go on to confess to all of the shootings and claim that "Sam" was a spirit who spoke to him through a black Labrador that belonged to his neighbor, who, it should be noted, was also named Sam.

However, a new Netflix docuseries, which is largely based on the writings of the late crime journalist Maury Terry, looks into the theory that Berkowitz likely didn't act alone — and that he was actually part of a wide-spreading Satanic cult.

It sounds outlandish enough that "The Sons of Sam: A Descent into Darkness" director Joshua Zeman said that, at first, he thought that it was just nonsense.

"Of course I didn't believe it," Zeman told Salon in a recent interview. "Not in the least. I thought it was all Satanic panic."

However, the more Zeman started digging into Terry's work, including his book about Berkowitz called "The Ultimate Evil," the more plausible it became. "And honestly, it scared the s**t out of me."

However, while some law enforcement officials agreed with Terry, and pointed to evidence that there had potentially been different shooters during some of the attacks, many just wanted the case to be closed. Amid the tension, Terry's reputation — and ultimately, his sanity — was under attack.

Zeman spoke with Salon about the making of the four-part docuseries, how the Son of Sam murders changed the face of tabloid journalism, and how Maury Terry made a "deal with the devil" in his reporting,

There are several main throughlines in "The Sons of Sam" that I want to talk about, but the one that was particularly interesting to me as a journalist was the way the business of news shifted after the publishing of the Son of Sam letters by reporter Jimmy Breslin. Could you talk some about how the case impacted journalism?

I think that's one of the most interesting things as well, especially as a true crime journalist. It wasn't just the investigation and it wasn't just Maury. I just think people don't really understand the impact that the Son of Sam story had on modern-day journalism.

In essence, journalism, true crime journalism and true crime changed with the Son of Sam. It started a tabloid war, which happened between the Daily News and the New York Post, but this is also where [Rupert] Murdoch realizes one of the most important lessons of his professional career: Fear sells better than sex.

You can look back and see that he was using the Son of Sam as kind of a test case. The landscape of journalism today — you can actually chart a path from "Son of Sam and that early fearmongering, which was coming from both sides, to the rise of tabloid journalism. It literally started like two or three years after Son of Sam with the rise of "A Current Affair," "Inside Edition," Bill O'Reilly, Maury Povich and that kind of reporting.

That idea, "fear sells," is so important when it comes to how true crime is made today.

Right, it definitely feeds into how we cover crime and serial murder. I think we are coming to a bit of a reckoning in terms of coverage and what it means. I'm not just talking about victim-blaming and some of the subtle things, but understanding what our role as creators and consumers is. I love true crime, I love true crime fans, but at the same time, I think we need to kind of understand what this all means.

It's interesting you bring that up because there is a point early in the series where, again, Jimmy Breslin appeared on television amid the Son of Sam' manhunt. He's talking about how people are interested in the murders and an interviewer poses the question to him, "Do you think that's a healthy interest?" How do you grapple with that same question as someone who is producing true crime?

I've done three true crime series and two true crime documentaries, right? I wouldn't call it "healthy," but for me, well — what's interesting about true crime isn't the murder part of it. It's what lies beneath the surface. It's the social stories and the social justice stories that we tell that lie underneath. Whether that's stories, for example, about how the internet was theoretically was supposed to make the world safer, but in the eyes of some sex workers, it makes it far more dangerous. Or how, in other cases, true crime allows us to look at law enforcement through a different lens.

It has shown us how much more transparent law enforcement needs to be.

[True crime] shows us how trauma goes and there's no such thing as closure. Like, I could tell you all the stories that I've learned and that's far more important than this kind of "murder" part of it — the blood splatter, the "CSI" effect, right?

This feels like an apt time to bring up Maury Terry. How did you two initially connect?

I had done a film about five missing children in my hometown of Staten Island called "Cropsey." While I was investigating that case, we kept hearing rumors from a lot of the cops and journalists that somehow these missing children were connected to the Son of Sam case and, more importantly, that Berkowitz didn't act alone. There was a cult behind him and that these missing children were connected to that cult.

I didn't initially believe it, but [after reading "Ultimate Evil"] I went to go meet Maury and I found him to be just this super interesting kind of character. He knew so much about true crime, especially in New York. He knew all about the cases that I was fascinated with, but he knew the truth behind them — what we didn't learn in the New York Post or the Daily News.

But at the same time, he had obviously fallen down the rabbit hole and, as a true crime journalist, I looked at his story as a cautionary tale for myself, but also a cautionary tale for everyone. He was so invested in the truth and the idea of truth. The most ironic thing is you end up having a serial killer telling him, "Look, dude, no matter how much evidence you have, the world is not going to believe you."

That moment blew my mind.

There's this moment in the documentary where Maury Terry described how he had a perfectly normal life before the Son of Sam case, but that it was almost impossible for him to go back to that normalcy. Having looked at this case and his writings closely, what do you think the tipping point for him was?

That's interesting. The switch, in my eyes, flipped right when the book came out because the police called him a crackpot. And, to an investigative journalist, that's the worst thing in the world. At the same time, I think there was this wave of Satanic panic flowing across the United States and suddenly, that movement looked to Maury for validation.

In turn, Maury found validation in the Satanic panic movement because, suddenly, here were a bunch of people who were willing to listen to what he had to say. He made a deal with the devil and sold his soul to the tabloid press in exchange for coverage. But tragically, I think that ended up undermining the veracity of his original investigation.

In the series, you spoke with a historian who studies the occult and he made the statement that once you start looking for symbols or messages associated with the occult, you're going to start seeing them everywhere. As a filmmaker, were you worried about falling down the same rabbit hole Maury did once you started checking into those connections?

It's funny, I didn't want to do the documentary at first because I was afraid of falling into that same rabbit hole that Maury Terry had fallen into. I didn't want to do it. I was like, "Oh my God, this guy — he's gone."

The irony of me saying that is that I've already fallen. In a way, doing this documentary was the breadcrumbs to find my out. It sounds kind of falsely meta, but it's not. Sometimes these cases become your life, and that's no joke.

It's alluring though, right? What's so interesting was going through all this news footage with the idea that Berkowitz didn't act alone. I was looking at it from a slightly different perspective and I would start seeing things and question, "Was that real? Was it not?" It was super fascinating.

I've seen a fair amount of true crime documentaries where directors have to obviously overcome not having archival footage of the event they're covering. You had a wealth of footage. What was the process of gathering and disseminating that footage like?

I originally didn't want to make this documentary, right? Despite Maury Terry telling me again and again — begging me to please do this documentary — I went off and made another series about the Long Island Serial Killer called "The Killing Season." While I was making that film, Maury Terry passed away.

Suddenly, I got a call from his family saying, more or less, "He left you his files." In those files was all this footage that he had, some of his numerous interviews with David Berkowitz. For some reason, he had never told me had those files. He never told me about the footage.

Suddenly I said, "Okay, now we can make a documentary." A lot of the process was just going through stuff and weeding it out. It was an embarrassment of riches, and then his book is a 600-page sprawling epic, if you will. The challenge was trying to get as much in there as possible while still telling a cohesive story. I could have done eight episodes so easily, honestly.

Speaking of Maury's book, how did you come to the decision to have Paul Giamatti narrate his writings?

I had worked with Paul at one point a long, long time ago. We had discussed that he has a certain affinity for the . . . esoteric. He likes things that are interesting and cool. And Paul just has a knack for embodying a character, whether on-screen or in audio.

And when Maury's family called me up, they said, "Wow, Paul Giamatti is so good. He was so good I forgot it wasn't Maury."

"The Sons of Sam: A Descent into Darkness" is now streaming on Netflix

Shares