1. Tin Huey T-Shirt

The day Patrick asked me for a divorce, I was wearing our Tin Huey T-shirt.

It is charcoal gray and the softest cotton, thanks to decades of wear. The neck is perfectly stretched out. Just above my collar bone, there is a tear along the stitching, giving the illusion that the rest of the shirt might spontaneously unravel and fall from my body, leaving me with nothing but a ribbed cotton necklace. There are holes everywhere: under the armpits, around my torso, on my back. My favorite hole is the one along the stitching of the left sleeve, forcing it to drape down over my left bicep and expose my shoulder, as though it were some elegantly crafted evening dress. Still faintly legible across the chest is "TIN HUEY" in stenciled, white acrylic letters, cracked throughout like an antique vase. No matter how much you wash it, it smells like people, rather than detergent. I don't wash it often, because I don't want it to disintegrate.

The shirt first came into Patrick's possession in 2003, when his band, the Black Keys, started garnering national attention, including a spot as the musical guest on "Late Night With Conan O'Brien." Tin Huey's guitarist gave it to Patrick hoping he would wear it on the show. It would be an honor, Patrick said. Patrick was obsessed with any rock band that ever came out of Akron, Ohio -- from big names like Devo and Chrissie Hynde to little-known acts like Chi-Pig, the Bizarros, and, of course, Tin Huey. His uncle Ralph had played saxophone in the band. Patrick remembers his grandparents always playing their only major label release, "Contents Dislodged During Shipment," on the hi-fi. But it wasn't simply the band's sound that enchanted Patrick. It was the possibility of creating something special in a seemingly unspecial town like Akron -- a place where people are not known for making art but for manufacturing tires. He cherished records like the Waitresses' "Wasn't Tomorrow Wonderful?" because they were definitive proof that maybe he could do the same.

The night Patrick first appeared on national television, I remember thinking, "I will never forget this moment." Sadly, more than seven years later, I have. In order to jog my memory, I search the Internet for a video of the performance. After several hours of sifting through the myriad of music videos, interviews and national TV appearances the Black Keys have made since, I begin to doubt that the moment ever happened at all -- that I had made it up entirely. But then, I find it -- a 3-minute, 34-second snippet of the Black Keys performing on "Conan O'Brien," Aug. 8, 2003.

The video clip begins just as Conan is saying "... guests from Akron, Ohio." The audience's cheers quickly fade into the signature riff of "Thickfreakness" -- a cascade of reverb echoing from the guitar of Pat's band mate, Dan Auerbach. I know that riff well -- I've heard it, literally, hundreds of times. I know when Dan has hit the wrong note, slyly sliding the fuzz into the right one. I also know when Patrick hits in too soon or too late on his drum kit. On "Conan," I notice that he hits in too early and is playing the song too fast, probably because he is nervous. Dan is forced to catch up. The audience probably has no idea -- but I do. Even seven years later.

When the camera finally pans away from Dan singing, I see that Patrick is, in fact, wearing the Tin Huey shirt and I'm ecstatic by this vindication. My memory is no fake. But my victory is too quickly displaced by a sudden surge of tears that surprise me as they stream down my cheeks. He looks so young. Our T-shirt is not yet full of holes. It fits him perfectly -- hugging his tall, fit frame. I can tell that I gave him the haircut he is sporting. I can remember how I used to cut his hair -- leaving it long in the front and close to the head in the back. I would cut it in the dining room of our apartment, while he sat in a chair, a hand towel draped around his shoulders. When I would shape his bangs, I'd often pause to kiss him on the lips, just before moving to the sides of his head, where I'd thin out the hair that sat over the arms of his glasses.

I am certain that he immediately drove home after the taping of the show so that we could watch it together. We would have been sitting on the turquoise futon in our living room in front of our hand-me-down TV. We'd be sipping on beers, high-fiving, and chain-smoking. He'd keep glancing over at me, looking for my approval as I stared at the screen, and then I'd pat his hands with giddy glee. He'd then point out that he played too fast and, even though I noticed it too, I'd kiss away his self-criticism and tell him it was just perfect. And then he'd say, with a glint of embarrassment in his tired, blue eyes: "Do you mind if I watch it again?" And I'd laugh at him and say: "OF COURSE NOT, DUMMY!"

And now, I must stop the clip and close my browser, because I'm suddenly overwhelmed with the memory of how good we once were -- a fact I don't allow myself to indulge, because it hurts too much. Because I don't know that boy anymore. Or that girl, for that matter.

So, instead, I try to remind myself of who we are now and why it's best that we are over. I think about the day he asked me for a divorce. Aug. 4, 2009. Just two days earlier, I had left for Warsaw, Poland, on a two-month research trip for a book I was writing. It was one of the few times in our relationship that I had done the leaving. I always feared that if we were both bouncing around the world for the sake of our careers, we'd never last.

Right before our phone conversation, I was awoken from a nap by a nasty dream. That's when I called him, the chalky taste of afternoon sleep still in my mouth. And that is when he said, in so many words, that he didn't want to be with me anymore.

"You mean, you want a divorce?" I asked.

As I sat there waiting for his answer, an ocean between us, I rubbed the cracked letters of the Tin Huey T-shirt into my chest, like salve into a wound, my worst nightmare before me.

2. A silk-screened poster from the Sept. 22, 2000, Mary Timony (of Helium) concert in Oberlin, Ohio.

I was 19 when we first started dating. Patrick was 20, just six months older. We had known each other since our sophomore year in high school. He was tall and lanky, with pockmarked skin and thick black-rimmed glasses. "An indie rock Abraham Lincoln" is how a friend once described him. We made a comical pair. I was half his size, though my face was just as long and angular. I was just as frenetic and mouthy.

It was one of the best summers I have ever had. We bought matching '70s roller skates from the thrift store and rode around parking lots late at night, his car stereo blasting Thin Lizzy or Pavement. We'd sneak into bars and order cocktails like sloe gin fizzes and Rumple Minze and then dance around like maniacs. We agreed that we were soul mates because we both loved coconut cream pie, salami with mustard, and Camel Lights soft packs. We made paintings, mixed tapes and fanzines, and planned for a future in which we'd always be doing that: making things together. We even started our own little band, just the two of us, sitting in his bedroom, writing silly pop songs about Vespas that we'd then record onto his four-track. In August, when I had to go back to Oberlin, Patrick cried. He didn't want me to go.

It was when he was up on one of his usual visits that we got word Mary Timony would be playing a show on campus. She was the reigning queen of indie rock, the former lead singer of Helium, who'd written one of our favorite songs, "Pat's Trick." "We should try to get on that show!" Patrick said. I handed the show organizers a tape of our songs and that was it. We were the opening act for one of our favorite musicians ever. That's how it always worked with Patrick. He always did what he said he was gonna do.

Patrick named our band Churchbuilder -- a bizarre and esoteric reference to "The Eyes of Tammy Faye," one of his favorite movies at the time. Unfortunately, we soon realized the limitations of my musical skills. For me, singing and playing keyboards proved as challenging as discrete math. Our little duo wouldn't be able to pull it off without help. We quickly recruited a couple of friends to perform with us. We taught them the very simple structures of our four modest songs and then, together, learned how to play "Tugboat" by Galaxie 500 as the final number. Five songs, 20 or so minutes. That would have to do.

That night at the student union, somewhere between the second and third song, I realized that I was enjoying myself. There was a rush to being onstage, having people cheer you on, stare up at you from the crowd like that, laughing at your stage banter. And then, after the show, strangers coming up to you, wanting to get to know you, genuinely excited to talk to you.

After that show, Churchbuilder continued for a bit longer. A small indie label out of Brooklyn, N.Y., put out our record, "Patty Darling." We played a handful of gigs throughout the Midwest and the East Coast. We were lucky if 10 people showed up, but we never cared. At least, I didn't. I had no designs on being a rock star. I wanted to be an academic, maybe a writer. But it was different for Patrick.

At the time, Patrick also began a project with a guy named Dan Auerbach. Dan and Pat had played music a couple of times in high school. I knew Dan because he lived across the street from my ex-boyfriend. Dan was a soccer jock who idolized Dave Matthews and G. Love and the Special Sauce. Bands I despised. He was a real macho type who walked around town like a bulldog. He listened to Howard Stern, called his girlfriends "babe" and referred to indie pop as "gay." I never did like Dan much. And I know he never liked me. He and Patrick were complete opposites with little in common except for one thing: insatiable ambition.

We kept little evidence of our time in Churchbuilder. I think its existence embarrassed Patrick once the Black Keys catapulted onto the A-list of gritty, serious rock bands. For Christmas one year, I framed the poster from the Mary Timony show along with a dozen Black Keys ones as his present. It ended up on the second floor of our house, in my office.

3. "Crazy Rhythms" by the Feelies (on white vinyl)

In the early days of the Black Keys, Dan's girlfriend, Tarrah, and I would accompany Dan and Pat on tour, not because it was such great fun, but because that was the only way we could ever see them. It would be the four of us, piled into Pat's baby blue Plymouth Voyager minivan that stunk of boys. Tarrah and I would help load equipment in and out of clubs, drive and sell merchandise at shows.

During one of the more grueling tours, the band played a show in Athens, Ga. Directly next to the venue was a record store that specialized in rare records. On the wall, they displayed a copy of the Feelies' "Crazy Rhythms" in white vinyl.

Patrick and I were huge fans of the Feelies -- tragic pop songwriters from the late '80s who gave up rock stardom for quieter lives. We particularly liked listening to them in the spring, while we sat out on the porch and pounded Belgian beer. The store was selling the record for $25. When Patrick saw the price tag, his face dropped. We couldn't justify spending that much. He shrugged and walked next door for sound check.

I stepped out of the store for a quick second to think. I lit a cigarette and rummaged through my bag for a bank receipt. My checking account balance: $14.28.

At the time, I had one credit card. A Discover card, no less. It had a $200 limit. About $50 of that was left. But the store wouldn't take credit. I went to an ATM and promptly withdrew what was left on the card, wincing at the thought of the inflated interest rate on such a cash advance. I then headed back to the store and bought the record.

After sound check, I gave it to Pat. His eyes almost bugged out of his head with guilt and gratitude. "But we can't afford this," he said. I just smiled.

In the end, when it came to dividing our 500 records, we didn't really fight. He told me to take what I wanted and leave the rest. I tried to be fair and remember exactly what I had brought into the relationship and what I had acquired, personally, during it. Bikini Kill's "Pussy Whipped" and Nico's "Chelsea Girl" were no-brainers, as were almost all of the bebop records that I had purchased during a "jazz" phase. He could keep the John Cale. And though I wanted to take Nick Drake's "Bryter Layter," it had belonged to his father originally.

The Feelies was the toughest to decide upon. Sure, I'd bought it for him. But there was so little for me to recover of what I gave that relationship. Most of my giving was immaterial. The Feelies record was the only tangible memory of my sacrifice, some physical evidence of my dedication.

A few days after I'd split up our records, he sent me an e-mail. "Did you take that Feelies record? I really want it. It has special memories for me," he wrote. "You bought it for me when we had no money."

"Exactly," I wrote back.

4. A big-ass dining room table

The day I went to our old house to separate records, I also had to place Post-it notes on every piece of furniture I wanted to take with me. The Post-it notes were his idea. He also told me to take anything we'd acquired as a wedding present, including the dining room table that we'd purchased with a gift certificate from one of his relatives. Funny, since I was probably the least ecstatic by the prospect of marriage in the first place.

Two years into our relationship, my parents got divorced. It was a nasty, protracted legal battle. By the time they finally signed the papers in 2005, my mother was basically homeless, my brother had suffered a nervous breakdown, and I found myself at the start of a drinking problem. As for my father, he ran off with another woman to Santiago, Chile, to begin a new life. A fan of marriage, I was not.

Still, when Patrick proposed, I said yes, because what girl would be dumb enough to refuse a marriage offer from the love of her life? Plus, we'd been together six years already and it seemed like the logical next step in a relationship I'd completely built my life around.

We were in Chicago when he did it. He was playing two shows there that weekend. He got us an extra-fancy room at a nice downtown hotel -- something really contemporary and swank with expensive lighting. We probably looked pretty goofy in that room, in our secondhand clothes that stunk of cigarette smoke. We overtipped the staff, a gesture that begged: "Thanks for not kicking us out." It was a far cry from the literally bloodied mattresses of the trucker motels in which we used to sleep.

He opened a bottle of champagne, while I lit a cigarette. He tried to get into a kneeling position, but, at 6-foot-4 inches, he was too tall to do it gracefully. Finally, he gave up, pulled a vintage diamond ring in a simple platinum setting from the chest pocket of his plaid thrift store shirt and asked me to marry him.

I acted as excited as I could, throwing my arms around him and then admiring the ring for as long as I figured any happy bride-to-be would. But inside, I was terrified. I wanted more than anything to want to be married to him. But it felt awkward -- like us in that fancy room. I suggested that we elope, but he said no, he wanted a proper wedding with all of our friends and family present. And that made me even more nervous.

When our wedding day came, my side of the chapel was sorely empty of relatives. My father didn't come, nor did any of his family. Not a single cousin, aunt or grandparent. My brother gave me away in front of my grandmother and my mother. And that was it for family. I made sure to get very drunk before walking down the aisle in order to numb the pain of their absence.

If someone deserved all of our wedding presents, it was Patrick's mother, Mary. In fact, it was Mary who planted the seed of marriage in Patrick's mind.

Just a few weeks before he purchased a ring, Mary took him out to dinner. She asked him why he hadn't proposed marriage yet and if it had to do with the fact that she and his dad had gotten divorced. She told him it was unfair to his entire family for him not to propose to me -- because they loved me and didn't want to lose me.

In many ways, the most enticing prospect of marrying Pat was belonging to his family. Despite their divorce, Patrick's parents managed to overcome their grievances. It was at our house that they celebrated their first Thanksgiving together in almost 20 years -- Jim and his wife, Katie; Mary and her husband, Barry. Soon, we were all vacationing together like one, big happy family.

It only seemed fitting then, that I used the largest Target gift certificate we received to buy something my new family would appreciate. I figured a large dining room table would do. It was rectangular and sturdy and could accommodate up to 10 people, eight comfortably. Before our marriage, I often hosted dinner parties for Patrick's family. They'd scatter about, balancing plates on knees, or eating standing up in the kitchen. Now, we could finally put them all at one table.

In the end, what hurt more than Patrick's request for a divorce was his mother's enthusiasm for one. In fact, it was a voice mail she left for him that signaled the end for me. I heard the message while I was sitting in my room in Poland, just after Patrick and I had talked about how he wasn't happy. I needed to know why. It wasn't my message to hear, but my respect for boundaries had been trumped by growing paranoia. She'd called to leave him the number of domestic court judges and divorce attorneys. "If you get a dissolution it will only take 90 days and if she's difficult, something like nine months. Well, that's it. Off to a girls' night out! Love ya! Bye!"

I can still hear the chipper tone of her voice in my head -- the nasal, Midwestern perkiness. It still makes my stomach turn to think of how complicit she was in all of it and how easy she made it seem to dispose of me.

As for the table: Whenever I look at it, I resent how much space it takes up. But I don't want to sell it or give it away, because I never want to have to buy another like it again.

5. The Futon

Shortly after I moved all of my things out of our house, Patrick called. "Hey, could you also take the futon in the spare bedroom?" he said flatly. "I don't want it."

His request stung. It made me feel embarrassed and dirty. Because I knew exactly why he wanted me to take it.

We had spent a good chunk of our relationship on that futon. When I was at Oberlin, Patrick moved it into my dorm room so that we wouldn't have to sleep on the super narrow, extra-long twin provided by the school. After college, when I first moved in with Patrick, it served as our living room couch, until we finally bought a real sofa, and it began serving as our guest room bed.

By that time, Patrick was constantly on tour. I knew he was leaving because he had to. These were opportunities not to be missed. But that didn't make it feel any better. I tried to keep busy with my job as a newspaper reporter. But mostly, I was sad and lonely. I started drinking by myself. I'd get good and drunk and then I'd call Patrick, crying and screaming. The next morning, I'd wake up with dread over my behavior, call him back, and apologize profusely. "You've gotta stop doing this," he'd say.

"I know," I'd respond. "It's just so hard sometimes."

"It's hard for me, too."

I never knew how to fix it. Then, I made it worse. It was the fall of 2004. I did not love the man I brought home, to our futon. That is not why I did it. I did it because I was furious for being left behind and scared of what Patrick could do to hurt me -- the sort of thing my dad did and the things Dan was doing to his girlfriend while she waited for him at home, putting her life on hold, just like me. I was a fool if I didn't think Patrick was doing the same thing -- even if I had no proof. I wasn't that special.

I remember sitting on the couch the next morning, nursing a 12-pack of Pabst to stop the shaking, thinking of what to do. I decided not to tell Patrick. It would devastate him. Instead, I decided to move out and dry out for a bit. I couldn't be a tour widow anymore. It was killing me.

A week later, I moved out. It was the week before I started a new job, the weekend of my 23rd birthday. Patrick wasn't home from tour yet. I had a few girlfriends help me lug the awkward futon down the back steps of our building and move my stuff just a couple of blocks away to a small efficiency apartment. I also started going to therapy, where I was diagnosed with alcohol-induced mood disorder, a diagnosis that I quickly dismissed because I thought I knew better. I thought, "I don't have problems because I drink. I drink because I have problems."

Patrick blamed himself, for all the touring, all the things he'd asked me to give up. He'd make it up to me, he promised. He'd show me how much I mattered to him. He'd stop touring so much, he'd say. Six months later, I moved back in with him, lugging my secret behind me.

Of course, nothing really changed, because nothing really does. Patrick started touring even more. I started drinking even more. And our fights only grew worse. There was beer thrown. I put a fist through a window. We crashed on the floors of friends' houses after long, drunken battles that would carry on into the wee hours of the morning. Our friends started to believe it was simply our strange form of foreplay.

Then, one night, I couldn't keep it in anymore. It should have been an idyllic night. Pat was home from tour. We'd just spent the day grocery shopping and setting up our Christmas tree. It was only four months after we'd gotten married. Things were supposed to be different. "Patrick," I said. "I have to tell you something."

I was extremely drunk when I made my confession, so I don't remember specific details. I know that I slept at a friend's house that night and that, when I returned the next day, shards of Christmas tree decorations were strewn across the living room floor. Patrick was nowhere to be found. I immediately walked upstairs and collapsed into our bed. I felt I had just ruined the most important part of my life.

Patrick tried to forgive me and we tried to move on, but we couldn't. The last year and a half of our marriage was dark and angry. Even after the divorce, I never could forgive myself for my infidelity. And the pages of the May 27, 2010, issue of Rolling Stone proved he couldn't either.

Then, one night, almost a year after we split up, Patrick called me. He sounded very drunk. And that's when he finally admitted that'd he also been unfaithful to me. Not just with the woman he'd left me for, but before that, even. One time, he said, on tour. He swore that it wasn't sex, just a bit of friendly fellatio, because, you know, he loved me so much he could never go all the way. "I swear that was the only time," he said. Oddly enough, I wasn't angry. I think I laughed. I was also glad that I didn't take the stupid futon, like he'd asked.

6. One audio MiniDisc of the Black Keys' first live performance, July 2002

This audio MiniDisc is a recording I made of the Black Keys. It is their first concert ever. I was one of only five people in attendance. I remember calling our friends and bribing them with shots to come and watch. The show was at the Beachland Tavern in Cleveland, Ohio, a cozy old man bar with Schlitz signs, $1 cans of Tecate, and a small stage that still plays host to a number of random garage bands, some that go on to great fame (the White Stripes) and some that don't (Churchbuilder). Since then, the Black Keys are much too popular to play the Tavern. They are now on the cover of magazines and win things like Grammy Awards.

For that reason, the MiniDisc could be valuable. I could sell it. I know there are some crazy fans out there who'd probably pay several hundred if I put it on eBay. Though, I'm not sure if the dissolution agreement would acknowledge it as my intellectual property or his. Legally, the MiniDisc probably belongs to him. His lawyers brilliantly made sure I had no claim to his musical legacy, despite helping build it. Nothing was said of my intellectual property in the dissolution agreement. It was as though I made nothing of value in our marriage -- nothing important enough to protect with legalese, at least. Still, I signed the dotted line.

But I don't hold onto the recording for its monetary value. I hold it hostage for a sense of what's possible. I keep it so that I can throw it away. I hold onto it because Patrick knows I have it and he likes to think in terms of monetary value. I would like to see if he sues me for it, because then that would prove that he is truly the monster I think he's become -- the monster I envision in my mind so that I will not love him anymore. I hold onto it with the idea that one day, I can mail it to his father, along with a 3x5 index card that says, "I thought you should have this." His father is a gentle man, and would be touched by my gesture, I'm sure. He loves memories. I think he still loves me. Also, if I sent it to Patrick's father, it would prove that I'm not greedy, unlike his son. The danger in sending it is that his father will give it to Patrick and then I will have no more power. I will have completely surrendered.

Mostly, though, I hold onto it because it is a beautiful and a horrible memory cast in sound. It was the beginning of something special. It was also the beginning of our end.

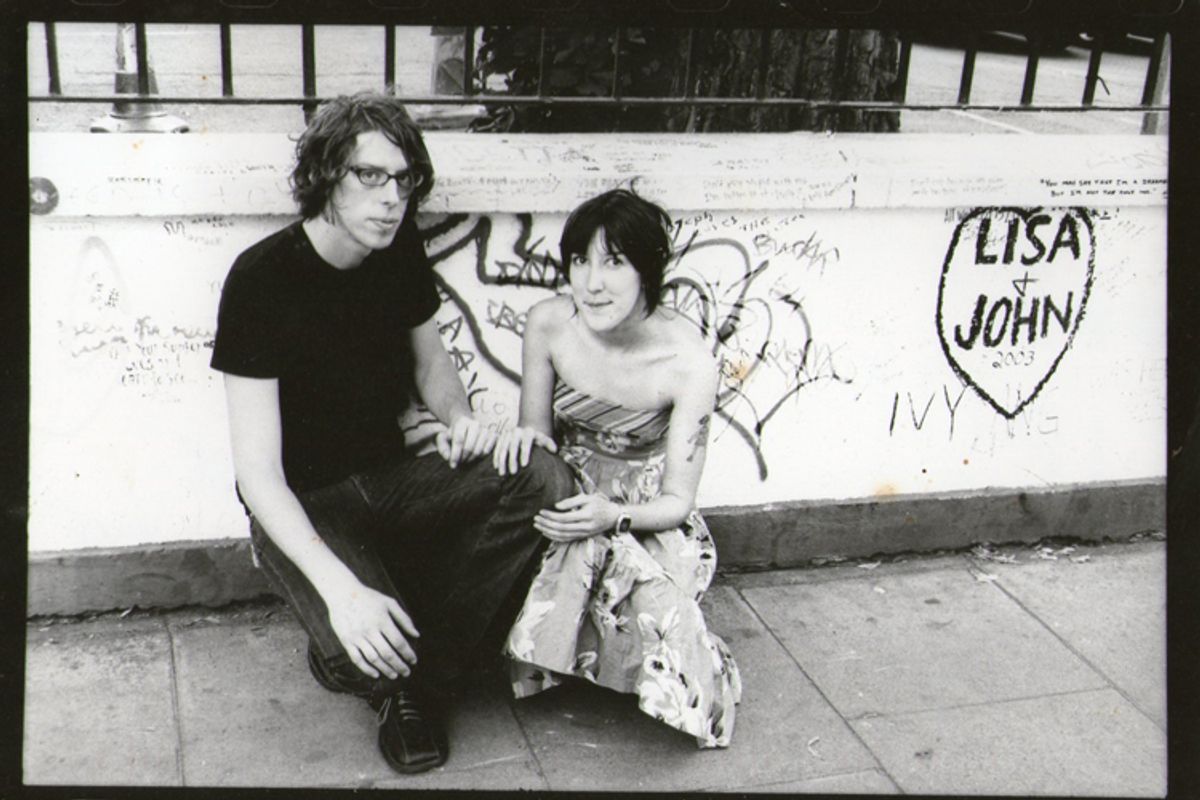

7. One black-and-white photo of Patrick and me, taken in 2003, at Apple Studios

In the year that Patrick and I have been divorced, I have taken to throwing a lot of mementos away -- notes I'd hung onto, photos of him as a child, photos of us together, mix CDs he'd made me, our wedding invitations, wedding cards, backstage passes from shows, anything with the words "The Black Keys" on it.

It is entirely against my nature to destroy evidence. I usually hold onto relics of the past with obsessive zeal. Each purging was painful. But people told me that I had to let go, and so I took them literally, and tried to put what was left of us in the trash.

We didn't have a ton of printed photographs of ourselves together. In fact, there were precisely three that hung in our house. One was of us kissing on our wedding day. The other two were almost exactly alike: us, in black-and-white, in front of the Abbey Road Studios in London.

The first photo was taken in the summer of 2003. Our friend Ben Corrigan took it. In it, we are both flashing genuine smiles in front of a wall filled with Beatles-inspired graffiti. I can tell we are having fun. Life is still an adventure. I might be hung over, but I'm muscling my way through, as I could only do at 22. Patrick is thin and handsome. His hair is long. I'm wearing some insane Hawaiian dress and a calculator watch. His hand is holding my hands, which are rested on his knee. A few months after it was taken, Ben had it made into a postcard that he then sent from London. He wrote, "I love you crazy bitches!" on the back. It was one of the greatest surprises I've ever received in the mail.

The second photo was taken five years later. This time, we actually got to go inside Abbey Studios, because the Black Keys were doing a Live From Abbey Road session. I thought it would be fun if Ben took the same photo of us before we left.

Unfortunately, it was freezing outside and we were in a rush to the venue where the Black Keys were performing that night. Patrick seemed resistant, but I promised it would be fun, so he begrudgingly went along with it. Ben e-mailed it to me soon after we got back. In it, we are all in black. Patrick isn't smiling, but wincing. Our bodies are turned into each other, but it feels so forced. If you set the two photos next to each other, it was so painfully obvious that we'd grown apart.

The day I moved out, I wasn't going to take any photos with me. But then I thought: What if, one day, I have a daughter? Will I have to tell her that I was once married to a man she will never know, but who was one of the most important people in my life? That I was once madly in love with a man who isn't her father, but with whom I wanted to have children? Would I then need to show her some evidence of this relationship?

And then, I thought: This is the picture I will show her, an example that things were not always so sad and heavy. In fact, they were wonderful once.

Shares