The last lyrics of Frank Ocean’s new highly anticipated and masterful "Blond" are “how far is a light year?” The answer, nearly 6 trillion miles, comes directly after some old spliced-together interview audio plays over art-school noise. But it speaks volumes about the entire album's concept in its simplicity.

A light year is a vast unit of measure — almost impossible to conceptualize — where time, distance, speed and dimension collapse upon one another. Short version: It’s super complicated, just like Frank Ocean’s new album and the version of queerness it presents, unattached to identity but solidly grounded in experience and the concept of unknowability.

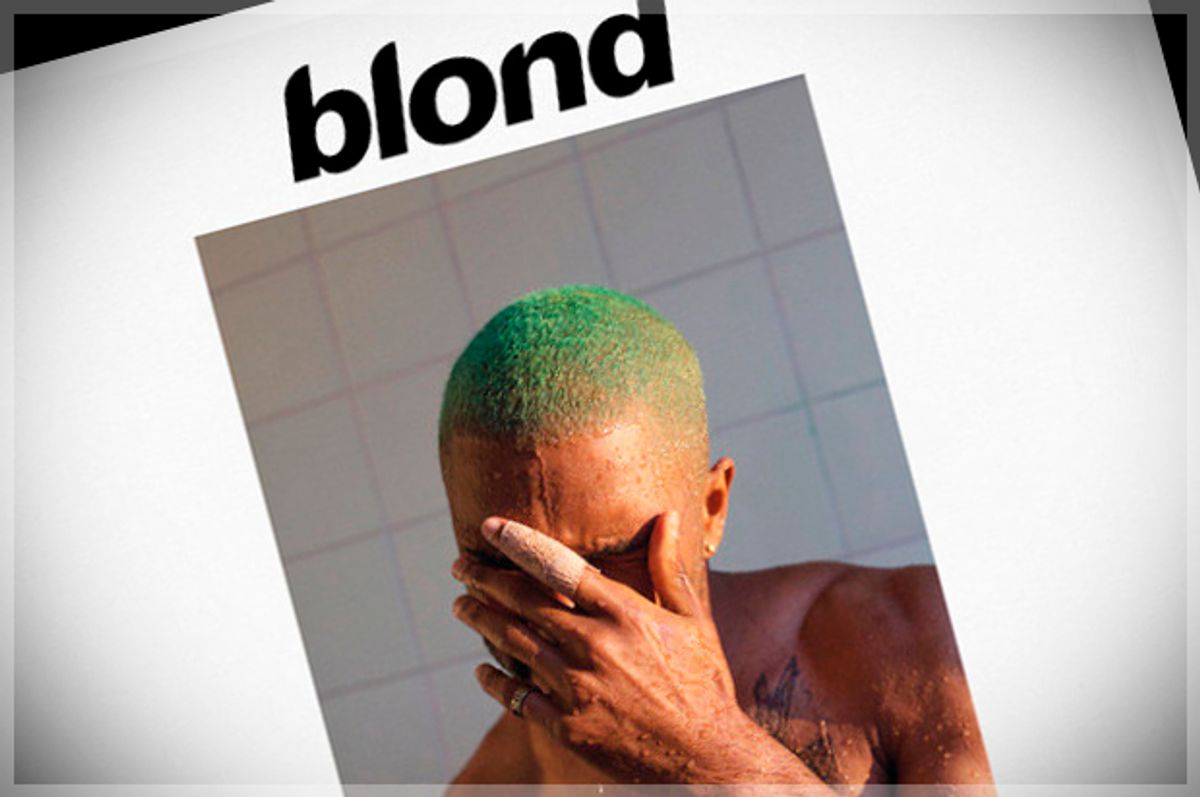

Frank Ocean has referred to this album as both "Blond" and as "Blonde" and I’m using the title Blond(e) here to denote a significant distinction between the cover art that references "Blond" and the online marketing and iTunes categorization for "Blonde."

"Blond(e)" is about the distance of a light year and attempting to shrink that distance, and it’s about the distance between individuals. That distance has particular resonance for LGBTQ+ communities because distance is what we have felt, being different in a world that doesn’t accept — much less celebrate — difference. "Blond(e)" is about not fitting in and trying to be oneself anyway, going against the grain.

It’s about not being contained, like light traveling through space. The basic dictionary definition of “queer” is “strange or odd,” and the power of Ocean’s "Blond(e)" lies in the ways it affirms being strange or odd since any degree of strangeness or oddness is defined only through limiting, normative rubrics to begin with. To listen to "Blond(e)" is to move through Ocean’s conceptualization of queer space.

Frank Ocean’s new album is queer as fuck but never through explicit identification — rather through the rejection of the very notion of identity. Ocean does not explicitly identify as gay, straight or bisexual. He has, however, openly expressed having had deep affective and romantic relationships with both men and women while simultaneously eschewing the labels that society puts on those dynamics.

He further confounds the public’s notions of what gendered and sexual labels mean in 2016, continuing much of the work that Prince did throughout his entire career in rock 'n' roll.

The new album"Blond(e)" uses specific references to “pussy,” “wet dreams” and “gay bars” to communicate a vulnerable innocence — a longing for a past when sex was a series of acts that people engaged in and not an internalized definition of who they were because those definitions can box people in and be used to control them. In this sense, "Blond(e)" is not all that different from Michel Foucault’s "History of Sexuality." Ocean’s work is best when it teeters between binary poles and definitions because it shows that those binaries and definitions are fictional and imposed on people to begin with.

The purposeful play between "Blond" and "Blonde" marks the masculine and feminine denotations of the words. Ocean’s original title for the album was "Boys Don’t Cry," which also invokes gender stereotypes, assumptions and expectations. The title's change to "Blond" or "Blonde" pushes the conceit even further because it forces audiences to see the opposite poles of an outdated gender binary and the shrinking distance between those poles, or conversely, the infinite expansion of those poles.

“Blond(e)” also references the distance between the past and the present, social media and in-person living, publicity and privacy, nostalgia and reality, youth and adulthood, freedom and constraint, the individual and society, as well as the space between who people are and what they want or hope to be. Essentially the entire album asks its listeners to consider a kind of queerness as the new normal — to focus on the spaces between rather than the points on a map.

Ocean’s songwriting asks listeners to imagine the possibilities outside of society’s prescriptions, the moments when they have challenged or doubted their sense of “self control.” Because what is self-control except adhering to norms that society teaches people to internalize? “Blond(e)” invites listeners to push past that and create connections with others in more vulnerable and organic ways.

In “Seigfried,” Ocean goes as far as positioning heterosexuals as settling for society’s rules. Saying he can’t relate to some of his peers, Ocean continues, “I’d rather live outside / I’d rather chip my pride than lose my mind out here / Maybe I’m a fool / Maybe I should move and settle down / two kids and a swimming pool / I’m not brave.”

Referencing a version of the American Dream that presupposes heterosexuality, replete with the kids and a pool, Ocean ironically highlights how brave he truly is for standing outside of expectations. While singing “I’m not brave,” turning the lyrics on their head through emotional repetition. The song ends with the powerful repetition of “I’d do anything / For you / In the dark,” alternating between sung and spoken vocal, chest voice and falsetto. This figurative battle between two poles illustrates his musical attempt to bring what can be done in the dark to the light — to queer the status quo.

Throughout the entire album, Ocean is trying to escape constraint almost like an ocean wave that crashes against the shore. Love, vulnerability and openness coalesce in a kind of nostalgia that imagines that people have moved past their current hang-ups about gender and sexuality. It’s intersectional and specific but with much to teach everyone.

Significantly, Frank Ocean’s hair is green in the cover art. For an album titled "Blond" or "Blonde," this simple visual complement shows him as neither side of the binaries referenced and moreover sporting a completely unnatural hair color. As an outsider, he’s encouraging people to exist in the in-between spaces, to embrace queerer possibilities than society offers, to connect with one another in those spaces by pulling closer, by holding one another closer as we free float together between those distances.

In “White Ferrari,” Ocean sings, “Mind over matter is magic / I do magic.” And he does. He creates a queer world where all people can thrive. And in “Godspeed,” he reminds people, “You’ll always have this place to call home, always.”

"Blond(e)" takes its listeners home and sets them free in uncertainty. So, again: “How far is a light year?” It’s right here. The audience is already there.

Shares