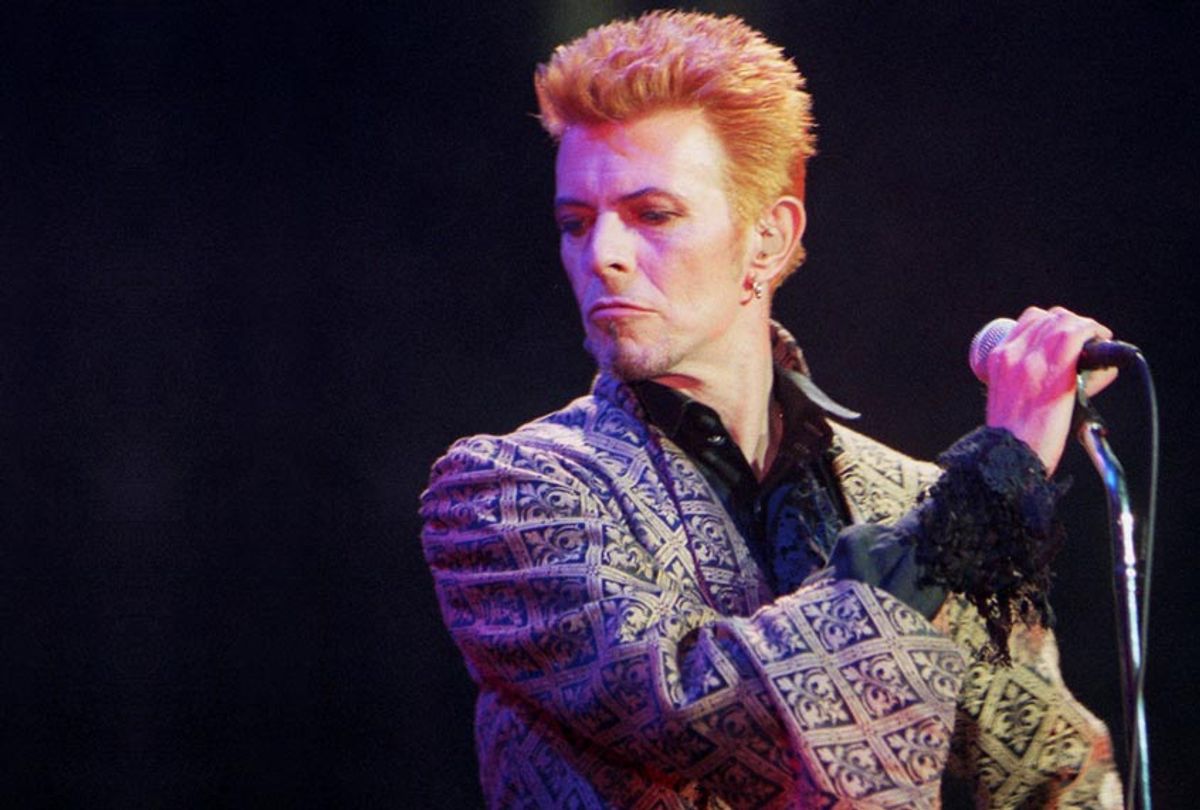

On April Fools’ Day, 1998, the crème de la crème of the New York art scene gathered for a party in the studio of Jeff Koons. David Bowie played host, and while a Who’s Who of the art crowd mingled over canapés and cocktails, the mastermind behind what would be (perhaps over-zealously) dubbed “the biggest art hoax in history” prowled the perimeters of the party. It was the key event to launch an elaborate practical joke concocted by Bowie and his friend, the Scottish novelist William Boyd, multi-award-winning author of numerous novels, most famously "Any Human Heart." Bowie and Boyd met while both members of the editorial board for Modern Painters magazine and quickly hit it off. Both were outsiders in the sense that they were art lovers but not involved in the art world directly, as a rock star and a star novelist. After a meeting in 1998, they bounced the idea around of introducing a fictitious artist into the magazine. Rolling with this idea, Boyd developed a fictitious history of a “lost American artist” by the name of Nat Tate.

With a novelist’s flair, Boyd developed a complete backstory for Tate: An orphan born in New Jersey in 1928, adopted by a family on Long Island, sent to art school and established in Greenwich Village in the 1950s. Tate met Picasso and Braques in France, but this triggered self-doubt, rather than inspiration. Returning to New York, Tate burned most of his oeuvre. Substance abuse and depression led to his suicide on 12 January 1960, aged only 31. It was a dramatic tale but one in touch with the history of art, which is unfortunately full of tragic stories of early deaths, from Giorgione and Raphael to Basquiat and beyond. It also conveniently allowed for the lack of documentation about the life of Tate, as well as the paucity of surviving works. But coming up with the story was the easy part. Building physical evidence to back the story proved much trickier.

In a recent issue of "The Journal of Art Crime," an article by Charlotte Rebecca Britton entitled “Forging a Double Life: Creating an Artist for the Purpose of Fraud” looked at an unusual phenomenon: “an artist being created for the purpose of promoting counterfeit art.” This is such an elaborate con that it has rarely been practiced, but her article (particular impressive when one considers that she had only recently graduated from the ARCA Postgraduate Program in Art Crime and Cultural Heritage Protection), cites several examples, one of them involving a hugely prominent name, and yet the case is strangely little-known.

To really make the story believable, Bowie and Boyd decided to publish a lavish monograph about the artist. Going with a publisher in Germany made it trickier for the anglophone public to ask questions. The friends reveled in the details, filling the book with plausible-looking footnotes, selecting historical photographs that they captioned as being of Nat Tate and his circle. Boyd, an amateur artist, even created some pieces to be featured in the catalogue as the work of Nat Tate. Bowie and Boyd recruited some celebrity colleagues who were in on the joke to offer bonafides and blurbs for the book cover, including Gore Vidal and Picasso’s biographer John Richardson. Bowie included a quote, as well, stating: “the great sadness of this quiet and moving monograph is that the artist's most profound dread — that God will make you an artist but only a mediocre artist — did not in retrospect apply to Nat Tate.”

The April Fools’ Day party in 1998 was officially the launch of "Nat Tate: An American Artist, 1928-1960," released as the first book from Bowie’s own publishing house, 21. Bowie read excerpts from the book and a British journalist, David Lister — who was also in on the joke — moved among the guests and instigated discussions about Tate, predicating his comments on the assumption that the party-goers had heard of Tate prior to that night. Apparently some of them had — a few guests could even recall having attended Tate’s exhibits in New York in the 1950s. Such is the power of suggestion.

This event was considered such a success that a London book release party was scheduled for the following week, but Lister was a bit too delighted with the proceedings. He broke the story of the hoax in The Independent before the London art scene could have the wool pulled over its eyes.

This story of a “forged artist” is not one suited to the history of crime, as no crime was committed. No one was defrauded out of anything — no one lost money. It was an elaborate practical joke, but one which Boyd felt made a good point about the naïveté of the art world. “It’s a little fable,” he wrote, “particularly relevant now, when almost overnight, people are becoming art celebrities.” The only kink in the scheme was Lister’s article, as Boyd and Bowie intended the hoax to be drawn out, perhaps with an exhibit of Tate’s remaining oeuvre at a major museum, and only to be revealed further down the line.

In Britton’s essay, she notes that the Nat Tate practical joke provides a useful roadmap for how some of the criminal artist forgers went about falsifying our impressions of history in order to profit. Appropriating quotes from celebrated figures gives the impression of veracity — if someone like John Richardson, the leading authority on Picasso, says that Tate was a great artist, there is much peer pressure to agree. Seeing is believing, and the inclusion of photographs and actual works of art (whether they actually have anything to do with the subject) help reassure readers, as do the presence of footnotes — which no one bothers to check to see if a) they actually refer to real publications, or b) if they refer to real publications, whether the referenced sources have anything to do with the subject at hand. Referencing evidence seems to be enough to satisfy almost everyone, as few bother to check the evidence referenced, to see if it is actually connected to the story at hand.

While Boyd and Bowie did not seek profit from their hoax, it did catapult Boyd from a well-considered, award-winning novelist into the status of talk show celebrity. And while they did not intend to make money of the works in question, an auction at Sotheby’s London in November 2011 sold a “rare surviving drawing from Tate’s Bridge Series, Bridge no. 114, which was bought for 7250 pounds. The profits went to a charity.

Shares