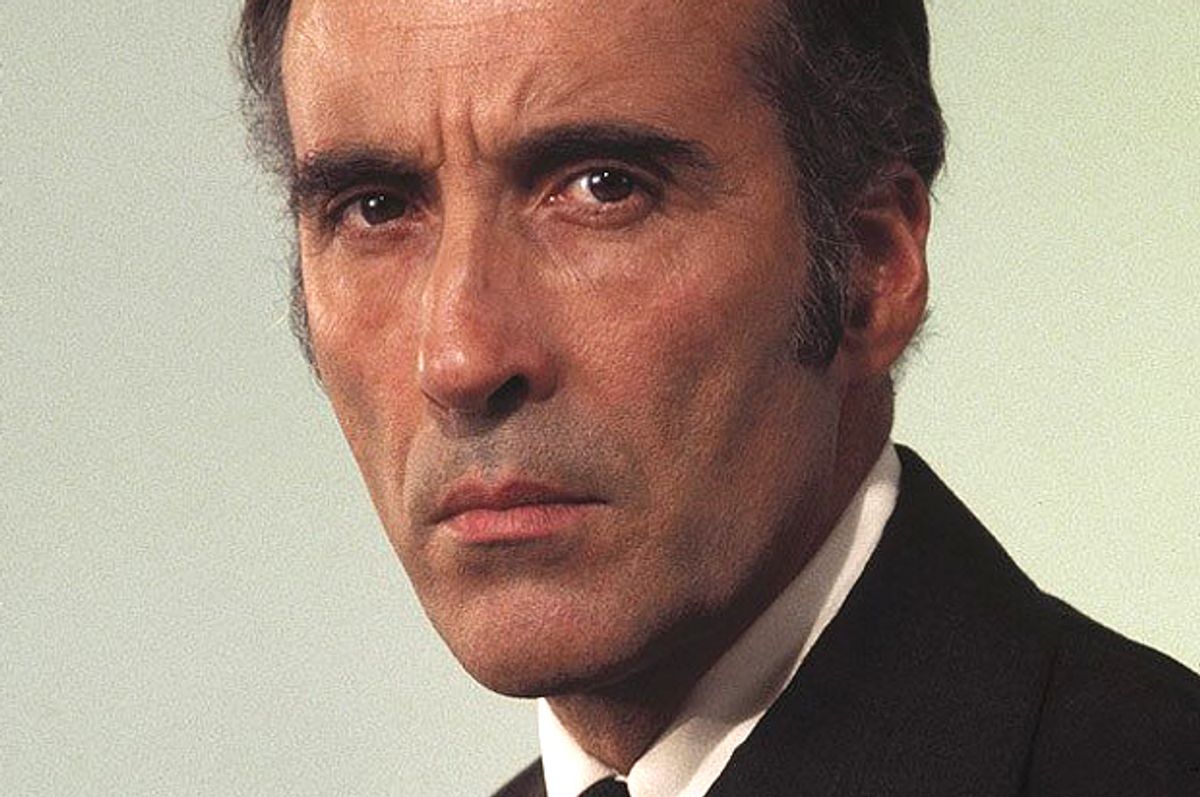

No one in the history of film has ever captured the irresistible erotic allure of corruption and decadence the way Christopher Lee did. That’s a strange endorsement and one that sounds limited in nature, but I don’t mean it that way. Typecast from an early age because of his height – at 6-foot-5, he was deemed too tall to play leading men – and his spectral, gloomy good looks, Lee alternately embraced the typecasting and battled it. Over the course of his long and prolific career – one of the longest and most prolific of any well-known actor, spanning nearly 70 years and roughly 280 film and television credits – Lee became one of the greatest screen icons of all time by playing infinite variations on the same theme.

The thing is, it’s one hell of a theme: the villainous aristocrat who sees into the true nature of things, and is willing to let you into the secret. For a modest price: Your soul, your life, your sense of reality and all that you supposedly hold dear. (Mwoo-ha-ha-ha!) That theme recurs over and over again not just in film, drama and literature, but also in history and politics. Donald Rumsfeld, in his finest moments of delirious pseudo-intellectual obfuscation, dazzling the Washington press corps with talk of “unknown unknowns,” was playing a villain who would have been played better by Christopher Lee.

We might say that Lee imbibed that attitude of aristocratic superiority with mother’s milk, except that it’s highly unlikely he ever had any of that. He was born in 1922 in the upper-crust London enclave of Belgravia, and in an entirely different epoch of British and world history. His father was a decorated military officer who had served in the Boer War and World War I; his mother was an Italian contessa famed for her beauty, who was repeatedly painted by high-society portrait artists. As a child Lee supposedly met the two Russian noblemen who had assassinated Grigori Rasputin, whom Lee would play in a low-budget historical thriller in the 1960s. Before he ever contemplated becoming an actor, Lee had a dazzling World War II career as a special-forces intelligence officer, fighting in North Africa and Italy and then hunting Nazi war criminals after the German surrender.

Lee’s remarkable life has now reached its end, with the announcement that he died last week in a London hospital, not far from where he was born 93 years earlier. But his career is still not quite over. He worked right to the end: He had recently completed work on both a live-action film and an animated voiceover role, and was preparing for a new film. It’s tempting to say that Lee was an immensely gifted actor (or rather that he became one with practice) who worked too fast and lacked discrimination, and who should have gotten the chance to tread the boards as Macbeth or the doctor in “Uncle Vanya” or whatever. OK, sure. But there are plenty of wonderful trained actors who can do that. There was nobody else – and there never has been anyone else – who could have played Saruman the White and Count Dooku and Count Dracula and Lord Summerisle in the 1973 horror classic “The Wicker Man” and dozens of other debauched lordlings in dozens of forgotten genre movies, and who could have found the precise register of overacting for each of them the way Lee did.

Again, “overacting” sounds like a criticism, when what I mean is overacting relative to the standard psychological realism of 20th-century dramatic acting. Lee understood that a certain grandiose falsity, an inflated and mythologized sense of one’s own importance where the sinister borders on the laughable (see above: Rumsfeld, Donald), was a central ingredient in most of the characters he played. He was virtually the opposite of a Method actor, but one could say he arrived at similar results by a different route. The distance between Lee and Jack Nicholson, even though one of them is quintessentially English and the other quintessentially American, is not as great as it first appears.

If we think we can see to the bottom of Saruman, the great wizard slowly eaten away by evil in the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, because we have read J.R.R. Tolkien’s books and know the story, the windswept gravity and tortured nobility of Lee’s performance constantly undermines our confidence. Saruman has fooled three of his immortal, semi-angelic peers for many years about his true nature and true intentions (spoiler alert!); who are we to presume that we understand the power relationships of the universe better than he? Saruman represents the most important chink in the moral buttresses of J.R.R. Tolkien’s binary Middle-earth, and while the book ultimately renders him not just evil but also petty and small, Lee never feels that way. His performance is one of the few areas where Peter Jackson’s films may be seen as improvements on the original.

If younger audiences will inevitably remember Lee as Saruman or as the regrettably named Count Dooku in the regrettable “Star Wars” sequels – I’m not saying he’s not good, only that the whole spectacle is a fiasco – those of us raised on 1970s late-night television will always associate him with his roles as Dracula in a seemingly endless series of low-budget horror films made by Britain’s Hammer studio. They can in fact be counted: There were seven Dracula films starring Lee, made between 1958 and 1973, and it’s only fair to say that from any vantage point the record is mixed. The best Hammer productions were classic examples of B-movie economy and atmospherics, and can still be enjoyed today on various levels, not all of them requiring beer goggles or MST3K-style quotation marks. I would tentatively vote for the 1958 original (released both as “Dracula” and “Horror of Dracula”) and “Dracula Has Risen From the Grave,” made 10 years later.

But Lee clearly felt himself above the material and repeatedly let the world know that, going so far as to claim that the reason he had no spoken lines in the 1965 “Dracula: Prince of Darkness” (in which the count only hisses) was because he refused to utter the inane dialogue written for him. That was almost certainly not true, but in some strange way Lee’s undisguised contempt for the entire franchise – he once said he could come up with 20 adjectives for it, but the list began with fatuous, pointless and absurd -- became part of its appeal. It certainly informed Lee’s performances, whether spoken or hissed, because who is Dracula if not a noble creature of Old Europe, who might have tolerated Lee’s decorous and well-bred parents but despises the mass of humanity and modern society?

Dracula in his Hammer form was an inherently limited role that Lee almost accidentally elevated, perhaps through the force of pure hatred. If he has a certain erotic allure or embodies the audience desire for negation and destruction, we are never tempted to see his worldview as wise or correct. Literally and figuratively, the coffin-bound count is a relic, a cummerbund-clad caricature from a bygone world who serves his purpose as a comic or ironic or threatening commentator on modernity before being once again impaled on the sharpened stake of the Age of Reason and reduced to dust.

Lee’s Dracula films for Hammer no doubt helped pave the way for the great vampire renaissance that began with Anne Rice, but I’ll leave that etymology to others. My point here is that the constraints and frustrations of the Dracula role are precisely those that Lee transcended as Lord Summerisle in “The Wicker Man,” probably the subtlest consummation of his craft and the high point of his pre-Saruman career. Seemingly a modern and worldly aristocrat who takes a benevolent view of the strange popular customs that hold sway on his Scottish island, Summerisle gradually reveals himself as a Byronic and/or Nietzschean genius who has gone right through the Age of Reason (and for that matter the age of Christianity) and come out the other side into a renewed relationship with sex and death and the rhythms of the natural world.

Lord Summerisle understands that the moral order represented by Edward Woodward’s increasingly hapless and tormented mainland policeman is a fragile construction set atop primal, animal realities, and inadequate to contain them. Does he believe in the old gods of his islanders? It’s not the right question. In his joyous amorality, Summerisle is Dracula set free from his box of Transylvanian dirt, Saruman set free from his labored parable of sin and damnation. He is the distillation of the mysterious and incalculable gift of Christopher Lee, expressed over and over again across an acting career that resembles no one else’s, and built on the profound understanding that we do not understand the world anywhere near as much as we think.

Shares