Whether Pope Francis can bring meaningful change to the Roman Catholic Church, and establish a new global role for that venerable, tarnished and internally divided institution, remains to be seen. But some things can be perceived clearly amid the gushing media coverage of the pontiff’s triumphant American visit, and the global lovefest that continues to surround his papacy. First of all, the semiotics and messaging of the Vatican are enormously altered under Francis – especially compared to his ghoulish predecessor, Benedict XVI, who openly longed for a shrunken congregation of zealots, eunuchs and old ladies.

Words and attitudes matter, especially the words and attitudes of a man believed by his followers to be infused with the Holy Spirit, and who traces his authority (at least nominally) all the way back to a fisherman who was given a new name by Jesus Christ. You don’t have to believe any of that stuff, needless to say, in order to grasp the importance of what Pope Francis demonstrated in Washington and New York this week: A spiritual leader can still play a powerful unifying role in the secular world, if only momentarily or temporarily, in a way that political leaders hardly ever can and hardly ever do, especially in the poisoned ideological climate of the United States.

Those ideological toxins propelled Republicans and Democrats out onto Capitol Hill after Pope Francis’ address to Congress, where they assured the cameras that they had heard two entirely different speeches and that the pontiff was really on their side. But the fact remains that the GOP leadership and the most virulent of Tea Party legislators were compelled to listen respectfully while Francis called for an end to the death penalty, the international arms trade and epidemic homelessness, and challenged the world’s supposed superpower to address the global climate crisis, welcome immigrants and combat the “cycle of poverty” that accompanies “the creation and distribution of wealth.” (Did he intentionally omit the sentence arguing that politics “cannot be a slave to the economy and finance”? We will never know for sure.)

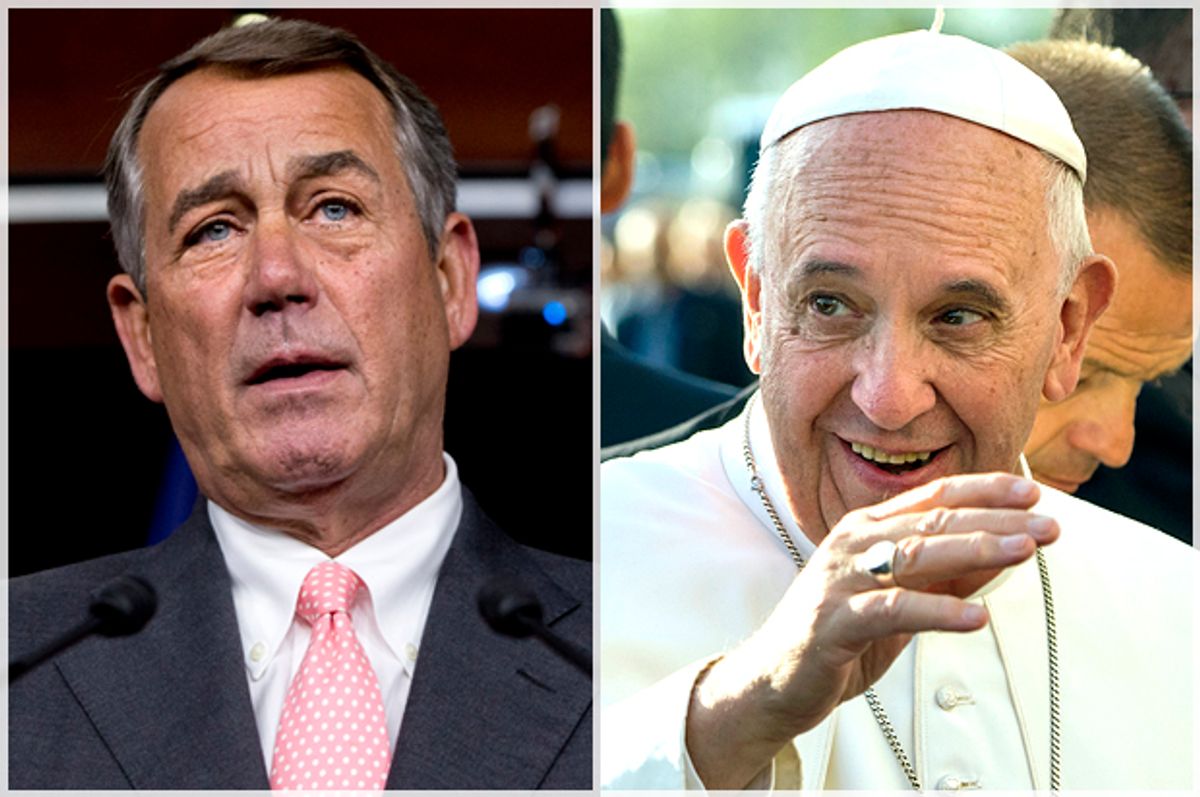

It may be unduly optimistic to hope that the pope’s speech provoked some genuine introspection among the entrenched antagonists of the Beltway, many of them so stuffed with lobbyist cash and high on shutdown fervor they have entirely forgotten that the outside world exists. Mitch McConnell is not big on introspection. If nothing else, Francis shamed the permanent paralysis and philosophical nullity of America’s political caste in the eyes of the world, which is no small accomplishment. Were those really tears of joy John Boehner was crying? Or was the unnaturally hued House Speaker reflecting on the fact that his political career was about to end in abject failure?

If we compare Francis’ brief papacy to the tragic and/or pathetic tale of Boehner, who has now been brought down by right-wing revolt after five years of nothingness, the differences are both illuminating and disturbing. Both men are constrained to a large degree by circumstances and institutions they cannot control, and the pope has the advantage of wielding nearly unlimited power, untrammeled by democracy. There is certainly intense political struggle inside the Vatican, and some ultramontane Catholics would cheer at news of Pope Francis’ downfall, as the crowd at the Values Voter Summit cheered when Marco Rubio told them that Boehner was toast. But those in the church hierarchy who hate Francis can’t simply vote him out; they would actually have to murder him, which has happened on numerous occasions but is more difficult to pull off these days. (We will set aside conspiracy theories about the 33-day reign of John Paul I in 1978.)

Still, it’s fair to say that one of those men has made an effort to step outside the internal politics of his institution, and to view it in terms of its global and historic mission. The other has been entirely devoured by political infighting, and never had any larger vision or sense of purpose in the first place. He will go down in history as the answer to an especially devious trivia question: Who was the Speaker of the House during its least functional era since the Civil War?

Taken entirely on its own terms, the Catholic Church is supposed to play a larger and more important role in the world than acting as the enforcers of an outmoded sexual morality or as a support system for tyrants and dictators. It’s supposed to be the leading exponent of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, a capacious and contradictory task that most popes of this century and the last one have studded with asterisks and steadily defined downward. Whether you like him or not, Francis is endeavoring to recapture that sense of larger mission.

Somewhere inside John Boehner’s brain, behind the scores of last Saturday’s golf foursome and the siren song of that bottle of Highland single-malt in his desk drawer, there may persist some awareness that the United States Congress was supposed to serve a higher purpose too. By all accounts Boehner is a decent guy and a Midwestern small-town success story, who wanted to play the traditional role of compromiser and back-room dealmaker. He may once have read about the discussions that led to James Madison’s Virginia Plan and the bicameral Congress created in the Constitution. The House of Representatives is supposed to be the most direct arena for the reflection of popular opinion, and the driving force of policy change. It’s where stuff is supposed to get done. Looking back at Boehner’s soon-to-be-forgotten tenure, we can only conclude that either that is no longer possible or he was not the man for the job (and quite likely both).

Of course we should not succumb too readily to Francis fervor, which presents a seductive but dangerous trap to many Catholics, former Catholics and “ethnic Catholics” like me. (I was never confirmed, but my father, my grandparents and many Irish generations before them were all Catholic, and I cannot deny a residual affiliation.) For many people, not all of them believers or even theists, Francis represents the possibility of spiritual renewal, a yearning that lies deep in human history and consciousness. To Catholics, he recalls the church of John XXIII and Vatican II, the church of Latin American “liberation theology,” the church that led Bobby Kennedy to get down on his knees in a California lettuce field in his Park Avenue suit, receiving Communion alongside Cesar Chavez and a team of immigrant farm workers.

Pope Francis is those things and is not those things; his positioning is highly calculated and politically astute. First of all, the new pope’s words and actions are obviously limited by his church’s tormented history and its encrusted dogmas. Francis is not going to revoke priestly celibacy, overturn the ban on contraception or reverse centuries of teaching on homosexuality overnight, and quite likely does not want to. He is not pro-choice or “pro-gay” or a feminist; he simply does not want to be held hostage by issues that make the church appear irrelevant. His canonization of the 18th-century Spanish missionary Junípero Serra, viewed by many Native Americans as a genocidal invader who enslaved their ancestors and destroyed their cultures, was at the very least a significant P.R. blunder for a pope who prides himself on speaking for the downtrodden and the oppressed.

All that said, it’s not fair to dismiss Francis’ loving and inclusive rhetoric, or his refusal to pronounce judgment against social forces and political movements repeatedly demonized by previous popes, as nothing more than lipstick applied to an enormous pig. Some activists in the Catholic Worker Movement apparently felt dissed by the pope’s brief reference to Dorothy Day, the charismatic and controversial co-founder of that most radical of all Christian social-justice organizations, in his Thursday address before Congress. I see their point, sort of: Francis pulled something of an MLK-style rebranding on Day, praising her for the strength of her faith and the inspiration she drew from the Gospel and the lives of the saints.

Francis did not mention that Day fervently despised capitalism and was an ardent pacifist who refused to pay federal income tax, or that Catholic Worker was (and is) essentially an anarchist political movement that understands its communal households as models for nonviolent social revolution. If any self-respecting Republicans in that chamber had actually heard of Day (or could understand the pontiff’s imperfect English), they should have stalked out in outrage. Day was arrested numerous times for direct-action protests on behalf of many different causes, was under FBI surveillance for half a century and repeatedly sided with socialist and Communist revolutionaries. She summarized her differences with them this way: Communists wanted to make the poor rich, whereas “the object of Christianity is to make the rich poor.”

As Sen. Bernie Sanders told a Washington Post reporter on his way out of the chamber, “The name Dorothy Day has not been used in the United States Congress terribly often.” Sanders, who is Jewish, may have been the only member of Congress who fully grasped the nature of the pope's reference. Now, is Francis trying to reframe Day as a less radical and more palatable figure than she actually was, 35 years after her death? (Day is under consideration for sainthood, which many of her followers do not want.) Well, sure. But here we have the pope – the honest-to-God Holy Father from Rome – telling the United States Congress that one of the four most important Americans he can come up with (alongside Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. and the Trappist monk and New Age mystic Thomas Merton, another striking choice) is a woman who devoted her entire adult life to a struggle against virtually every aspect of America’s economic order and foreign policy.

One may reasonably ask how much Dorothy Day actually accomplished, and how much Pope Francis’ more measured and modulated efforts to drag the Catholic Church into the modern world will accomplish. Day died the year Ronald Reagan was elected president, and if she has been watching America from above, she must have burned down Heaven in outrage several times over by now. But she also knew that the future lasts a long time, and that to die in dishonor and be forgotten or misunderstood for years afterward is often the lot of saints and prophets.

Pope Francis is not likely to shame his Republican co-religionists into acknowledging that climate change and economic inequality are the results of human decisions and not the will of God, and that to ignore the mortal danger they pose for our society and our planet is un-Christian, in the truest sense of that word, and also inhuman. At least not anytime soon. But as the right-wing counterattack against the pope’s American speeches has made clear, he has profoundly unsettled those who thought they had the system wired, and who assumed that the sinister alliance between corporate capitalism, evangelical Protestantism and the Catholic hierarchy had become an enduring bulwark of conservative politics.

Making those in power uncomfortable, and bringing them face to face with the moral consequences of their actions (inaction, after all, is a way of defending the status quo) is an urgent and necessary task. That’s supposed to be our job, according to the grand Enlightenment theories about democracy. But when you have given up on democracy to the extent that John Boehner has somehow wound up in charge, bereft of anything resembling ideals or principles and unable to get anything accomplished, it seems reasonable to appeal for divine intervention. (Although I have to say: If God talks to this pope and also whispered to Pope Benedict, that supports my dad’s contention that the Almighty is an Irish barroom drunk who keeps forgetting what he just said.)

Of course we should not and cannot rely on the autocratic ruler of an antiquated and deeply problematic religious institution, with numberless piles of skeletons in its closet, to save us from the profiteers and the plutocrats, the warmongers and the apostles of hatred. But somewhere down near the core of our species consciousness we long for salvation, for spiritual rebirth and for moral leadership. That longing may be irrational in itself, and may lead us in all kinds of irrational directions, but the Age of Reason has failed to find a lasting cure. Pope Francis, of all unlikely people, has answered that call, and if anything we are a little too grateful. John Boehner heard the call too, through his orange haze of country-club cocktails and defeat, and could only weep.

Shares