Let’s recognize what a brave and daring act Doug Liman has undertaken in remaking “Road House” especially considering, and I am simply repeating what I have been told, that “Road House” is to white men over 40 what “The Color Purple” is to Black women.

Think about it, I was also told by that person, mainly to prevent me from reflexively slapping them for suggesting such blasphemy. Each movie’s hero overcomes the darkness of their past and calls on stores of resilience to surmount overwhelming obstacles. Well, sure. You can say that about any number of movies.

But while Alice Walker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning story exalts the power of sisterhood to mend intergenerational wounds inflicted by racist violence, misogyny and all variety of physical and emotional abuse, the 1989 multiple Golden Razzie Winner preaches, “Pain don’t hurt.”

Separating the mental from the physical, and thought from feeling, is noble. Explains a few things, doesn't it?

One important omission robs the new “Road House” of that spice that made the original magnificent — Gyllenhaal’s Dalton does not have a Ph.D. in Philosophy from NYU.

The 2024 version of "Road House" is not all that. Although it follows the basic architecture of the original, enough has been changed that it loses the cellular bro-appeal of the Patrick Swayze masterwork. Casting isn't the issue. Taking over for the late Swayze, bless his soul, is an extremely ripped Jake Gyllenhaal, whose Elwood Dalton is an appealing down-on-his-luck former mixed martial arts fighter with a sunny disposition, a grim secret and a shredded core.

Jake Gyellenhaal in "Road House" (Laura Radford/Prime Video)What he is not is a highly in-demand bouncer in the bar rescuing business, just as the new dive in distress isn't classily named the Double Deuce. It's a beachfront bar in Florida – that might as well have been regurgitated from the unsettled belly of a Jimmy Buffet tune – called . . . wait for it . . . the Road House.

Jake Gyellenhaal in "Road House" (Laura Radford/Prime Video)What he is not is a highly in-demand bouncer in the bar rescuing business, just as the new dive in distress isn't classily named the Double Deuce. It's a beachfront bar in Florida – that might as well have been regurgitated from the unsettled belly of a Jimmy Buffet tune – called . . . wait for it . . . the Road House.

This new Dalton steps up to help a nice lady named Frankie (Jessica Williams) who is right to see potential in her thatch-roof bar. If not for the predatory biker gang messing up in the place on a whim or the randos beating each other silly, it could be rented out for weddings or tiki-themed bar mitzvahs, you name it! As it stands, though, fists can start flying for any reason at all, or no reason whatsoever.

But one important omission robs the new “Road House” of that spice that made the original magnificent — Gyllenhaal’s Dalton does not have a Ph.D. in Philosophy from NYU.

If he does, he doesn’t list that in his medical file that he carries around with him from town to town. As one does! But that detail lends a strange raison d'être to this movie.

The longstanding joke about philosophy degrees is that they are pointless, unless the goal is to live in your parents’ basement or pursue another degree in a discipline that’ll actually pay your bills.

“I want you to be nice until it's time to not be nice."

The New York University Department of Philosophy’s website begs to differ. It insists their undergraduates are prepared for “the many professional pursuits that benefit from critical thinking, analysis and argumentation (including education, law, medicine, politics, business, computer science and publishing) and for the kind of life deepened by awareness and reflection that is most worth living.” Arm bars and joint locks are sold separately.

We need your help to stay independent

As Friedrich Nietzsche observed, “When a man feels that he has a divine mission, say to lift up, to save or to liberate mankind; when a man feels the divine spark in his heart and believes that he is the mouthpiece of supernatural imperatives . . . it is only natural that he should stand beyond all merely reasonable standards of judgment.”

Ergo, if one were inclined to read a more layered significance in a movie directed by Rowdy Herrington, Dalton’s intellectual baseline explains his burning devotion to restoring America’s honor by beating the drool out of sweaty, handsy boozehounds and letting the local Jezebels know they don’t have to rent out their boobs for $10 a squeeze.

When he shows up at the Double Deuce in Podunk, Missouri U.S.A., it’s the kind of place “where they sweep up the eyeballs after closing,” the owner says. The crooked-toothed filthy patrons can’t keep their tongues in their mouths and break everything in sight.

But Dalton has standards and ways he teaches to the resident bouncers, and soon enough they are bathing regularly and methodically taking out the trash.

“I want you to be nice,” Dalton tells his rough prairie diamonds, “until it's time to not be nice."

Conor McGregor and Jake Gyellenhaal in "Road House" (Laura Radford/Prime Video)Gyllenhaal’s Dalton is also nice, but in a Dexter Morgan, “you will never find the body” kind of way. He smiles at the people whose bones he’s about to break and even offers to drive them to the hospital after he completes his job.

Conor McGregor and Jake Gyellenhaal in "Road House" (Laura Radford/Prime Video)Gyllenhaal’s Dalton is also nice, but in a Dexter Morgan, “you will never find the body” kind of way. He smiles at the people whose bones he’s about to break and even offers to drive them to the hospital after he completes his job.

“Nobody ever wins a fight,” he solemnly tells the hot E.R. doctor who patches him up, echoing the words of Swayze’s sunrise tai chi practitioner.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

His niceness opposes that of Knox, an unruly, psychotic hired killer appropriately depicted by Conor McGregor, an actor and MMA star associated with multiple assault cases who’s pretty much just being himself. The contrast between the two men is explained in the last scene when a wise little girl at the bookstore Gyllenhaal's Dalton frequents tells him that he may not be the hero, but he’s not the villain either.

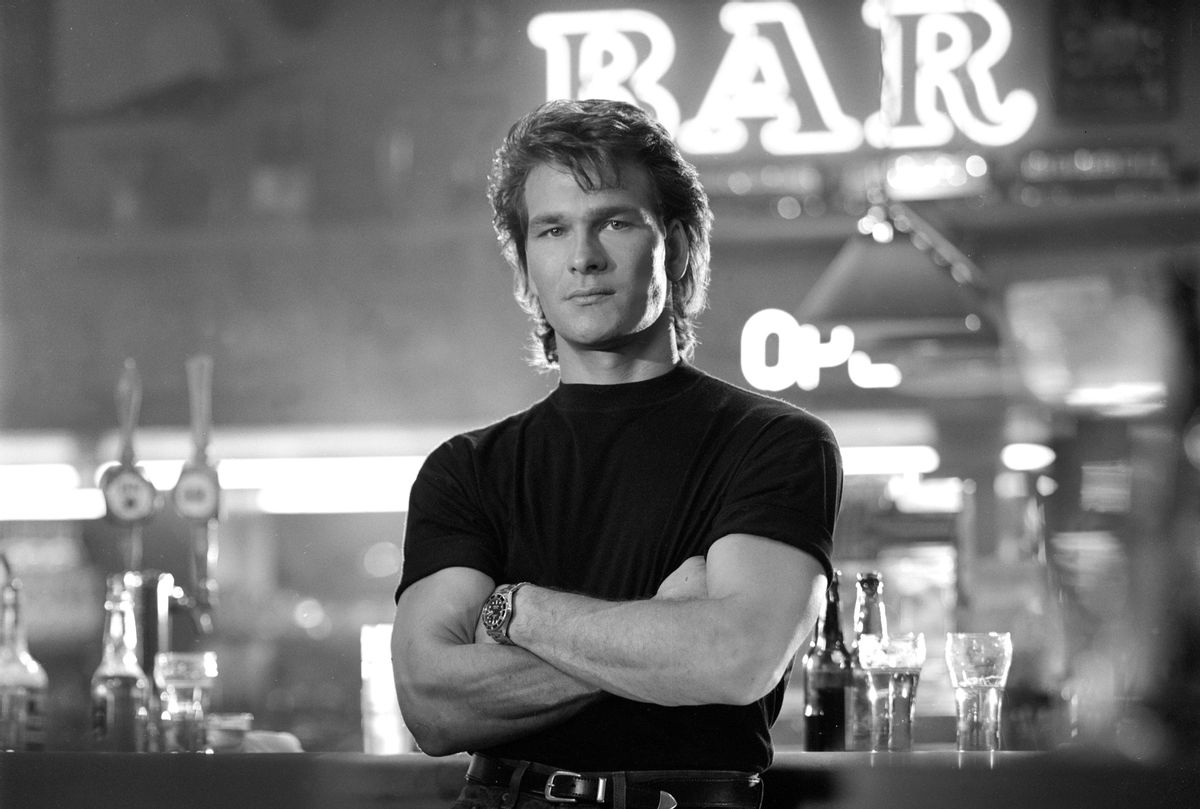

Patrick Swayze tends to a wound in a scene from the film "Road House" (1989) (United Artists/Getty Images)

Patrick Swayze tends to a wound in a scene from the film "Road House" (1989) (United Artists/Getty Images)

By the end of the movie Swayze’s "cooler" has stopped a JCPenney department store from ruining the town’s all-American tanginess, or whatever, and heads off to spruce up some other fetid swill hole. Gyllenhaal disappears on a bus to walk the Earth. Like Caine from “Kung Fu,” or Jack Reacher, or some broke dude who can’t find a job with his philosophy degree.

The original Dalton explains philosophy to his Doctor Girlfriend as “man's search for faith, that sort of s**t” which, I’m sure, is precisely how a tenured NYU professor would love to hear his life’s work and teachings summed up. She asks: How did he end up as a bouncer?

“Just lucky, I guess,” he says.

That’s about as philosophical as that “Road House” gets, and more than we receive in the new one — and let's be honest, all either aspires to be is a dumb good time. Nevertheless, it’s a shame that removing an integral piece of nonsense that, in its own way, makes us think. And laugh.

"Roadhouse" is streaming on Amazon.

Shares